For a real review of this fine work, see The Atlantic. These here are just some notes to self so I don’t forget that I just read a 500-page book.

I’ve just finished reading The Fellowship, by Philip and Carol Zaleski, a group biography of the Inklings, which evokes with extraordinary clarity images of clubmanship and bonhomie the group enjoyed between the wars. Not much of the material was new to me, having taught C.S. Lewis and the Inklings for the University of Washington, and having read biographies of Lewis by George Sayers and Alan Jacobs, as well as Lewis’ own Surprised by Joy and his Collected Letters, but the enigmatic figures satelliting the myth-maker (try as they might, no one manages to get Lewis out of the spotlight) find rather fuller expression here than they had had for me, and the group’s travails are depicted with the sympathy I think they deserve in this lively, ambitious book.

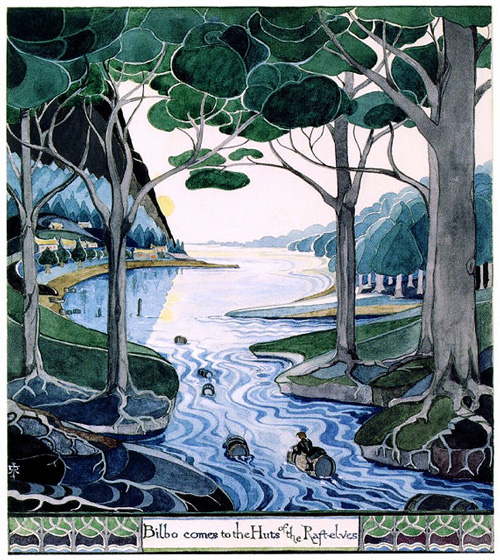

Clearly both researchers and fans, the Zaleskis sometimes blur the lines, allowing their affection for the characters (which who can fail to feel?) to overwhelm accuracy of assessment. For example, Tolkien dabbled in watercolors, and was a pretty fine draftsman, but his work doesn’t deserve the hushed tones the Zaleskis offer it, as though the world had ignored another Van Gogh in failing to grant him fame for it. Likewise, they discuss Lewis’ poetry as though it compared favorably to T.S. Eliot’s. They might even have been equal talents, the Zaleskis imply, had not public tastes shifted toward the modern under the don’s feet. But that’s not so. Lewis was wretched as a poet and as soon as he realized the fact, his whole world (and ours) grew richer.

Though they seem to have a hard time uttering criticism about these heroes, the Zaleskis rarely flatter concerning personal matters; a restraint I appreciate. Most biographers either ignore Warnie’s alcholism or wag thier fingers at him, as though dipsomania were fit subject for Sophoclean tragedy. The Zaleskis do neither, speaking plainly and seriously about his many hospitalizations without raising the proverbial eyebrow whenever we see him serving drinks.

They show a little less restraint on the subject of women, especially Dorothy Sayers, a tough, intelligent, successful, and deeply-admired figure who they have standing a the bottom of a tree house weeping at a hand-scrawled sign reading “No Girlz Aloud.” Several times they repeat the fact that no women attended Inklings meetings, but gentlemen’s clubs existed in the early twentieth century, as did ladies’ clubs. We need no more sigh at their social divisions than mock them for their ridiculously sluggish internet connections, especially when the circumstances so obviously suited all concerned. Who, seeing the Inklings’ corporate output (including Sayers’), could wish they had done things differently?

The Zaleskis give us an academically-robust Tolkien, which is a pleasant update to the picture Hobbit fans sometimes have of a professor phoning in his academic duties in service of his real passion for fantasy. And they give us also a Tolkien beautifully devoted to his family. He took each of his children on walks separately, for instance, acknowledging that they were different people with individual needs. About his wife Edith Tolkien believed:

‘nearly all marriages, even happy ones, are mistakes,’ as a better partner might easily have been found, but that nonetheless, one’s spouse is one’s real soulmate, chosen by God through seemingly haphazard events. Edith despite her lack of intellectual depth, her religious recalcitrance, and her fading beauty, was his real soul mate, and to her he pledged his body, his energies, his life (211)

The Fellowship also corrected my Lewis timeline somewhat. I knew he did well during his life, but didn’t have a sense of how popular Screwtape Letters made him. That many of the Christians who admire Mere Christianity did so first as radio broadcasts I knew, but not what blockbusters were the broadcasts themselves. I also liked Joy for the first time, who Debra Winger plays as Yoko Ono in the beautiful film Shadowlands, and who always seems like a hustler. She still reads partly that way, calculating circumstances so that she could ensnare the wealthy and famous writer, but in Zaleskis’ portrait, she’s so intelligent and successful in her own right that their partnership makes more sense than it had for me previously, and than it ever did for Lewis’ friends.

Finally, I like that the book showcases Oxford. The Inklings couldn’t have happened anywhere else and the city gets its due here; rather than stressing Ireland as some have done, or even the Kilns as others have, the Zaleskis give us a set of lives tangled around each other and an actual tangle of streets in that magic, holy place.