The Spasmodics’ Social Anxiety Salve

I’m presenting a paper at the Fall 2016 gathering of the North American Victorian Studies Association (NAVSA) hosted by the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at ASU on the theme of “Social Victorians.”

I’m looking forward to it because, while I regularly present at the North American Society for the Study of Romanticism’s (NASSR) conferences, and though I’ve presented on the Spasmodics before in other contexts, this will be my first NAVSA. Here’s my pitch, the full presentation of which will be given in Phoenix in November:

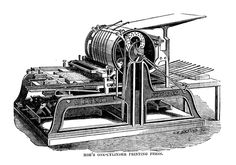

The reluctant founder of the so-called Spasmodics, Phillip James Bailey, trained as a barrister before turning to compose his enormous and enormously popular poem Festus (1839). For a book both long and difficult, full of grand abstractions and abstruse theological musings, Festus was a hit, to quote one early reviewer, “even among those who do not usually go in for poetry,” a popularity that began with its very first public reading, conducted by the mechanics working the printing presses and binderies on which it was produced. The book became a social object as soon as it became a book, and Bailey’s home became a social space, a place of pilgrimage almost immediately thereafter.

One such pilgrimage was made by Alexander Smith, inheritor of the Spasmodic mantel, whose first book A Life-Drama (1853) likewise blurred social barriers, this time, within the text. Poets and prostitutes blend therein with aristocrats and even goddesses in a drama not only of one person’s life, but of social life in Britain generally. Like Bailey’s, Smith popularity cut right across classes, the working-class writer a guest of nobility immediately following his book’s publication. Here too, the book became not only a social object, but a ticket for its author into new spheres of sociability.

As Antony Harrison and Charles LaPorte have noted, the Spasmodics touched off a kind of Victorian culture war in criticism, but, this paper shows how their books also created radically new social–from their radically new artistic–forms.